Tucked in gentle rolling hills on the brink of the Bootheel, the Bloomfield Cemetery tells a story. The chapters unfold one-by-one on the white tombstones of Confederate soldiers from around Bloomfield who died during the Civil War. Many are now laid to rest on this beautiful spot atop Crowley’s Ridge, a towering geologic oddity that slices across southeast Missouri, separating the hill people from the flatlanders.

Some of these headstones represent soldiers who were killed in action. Some never made it home to rest in the cemetery. Regardless, all have a story to tell, and the tombstones provide a glimpse. Some soldiers were “executed by parties unknown,” or “murdered while en route home.” But the vast majority died of illness. Alas, details on headstones can only scratch the surface of deep family tragedies. Private James Horton died of illness in the Union’s Rock Island Prison. Private Johnathan Horton died of illness at Gratiot Prison in St. Louis. Private Jesse Horton died of illness as a POW in Alton, Illinois. And a man old enough to be their father, John Horton, died in Gratiot Prison. All were cavalrymen in the same unit. Reading the inscriptions, I sensed that in the 14 months spanning the deaths of these POWs, there were four widows in the same family.

So far as I know, this is the only Civil War cemetery in the nation where the tombstones tell how each soldier died. “Noted guerrilla” John Fugate Bolin was captured, imprisoned in Cape Girardeau and hanged by an angry mob on February 5, 1864. Private George Baker “Deserted CSA, Joined USA, Captured by CSA, Hanged by CSA.” Private Jacob Foster “died of wounds received at Christmas dinner, Doniphan, MO, Wilson’s Massacre.” One inscription reads, “Accidentally killed. Kicked in head by horse.”

A long view of the rows of tidy white stones belies the chaos that reigned over this area during the Civil War. Up close, the stones tell personal stories. Aboard the ironclad C.S.S. Arkansas, Private Smith Minton saw a shipmate decapitated by an enemy shell. When the captain ordered him to “throw that body overboard,” Smith Minton replied, “I can’t sir, that’s my brother.”

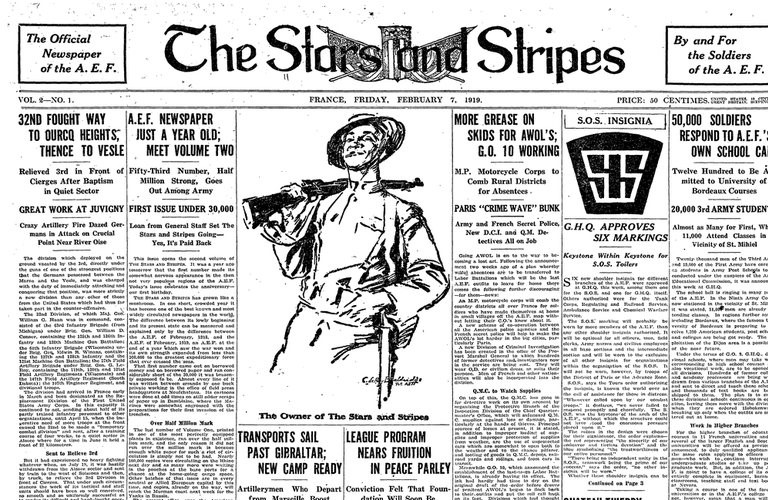

It seems natural that Bloomfield would put extra information on tombstones. Long before there was an Armed Forces Radio, the town spread news to uniformed troops through the Stars & Stripes newspaper, first published here on November 9, 1861. That’s when young Brigadier General Ulysses Grant was prosecuting the nearby Belmont campaign against the Confederates. Grant ordered 2,000 troops to eradicate the rebel forces in Stoddard County. Union invaders found the abandoned newspaper office of editor James Hull’s Bloomfield Herald, where they cranked up the press to publish some camp news. Today, Bloomfield’s Stars and Stripes Museum Library honors that event and nearly 150 years of subsequent issues of the newspaper, delivered into the hands of America’s service men and women worldwide.

Editor Hull is buried here, too. An orderly sergeant in the Confederate 6th Missouri Infantry Regiment, he died in 1863. The headstone doesn’t say how he died; it simply lists him as “editor, Bloomfield Herald, Birthplace of the Stars and Stripes Newspaper.” –from A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart

Share this Post