“That there’s not a skunk,” the guide pointed to one animal pelt on a table, “That’s genuine Alaskan sable.” It was a skunk, the guide admitted, but to the European fur market in the early 1800s, the term Alaskan sable sold better.

“See that coonskin cap over there,” the guide continued. “Nobody around here wore coonskin caps. But they were sold back east as genuine frontier wear.”

Frontier fake news.

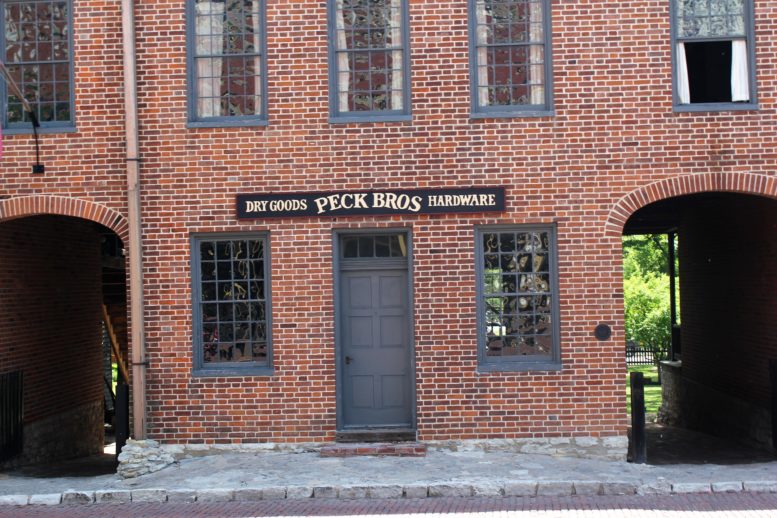

When Missouri’s first legislators met in Saint Charles, they walked into this dry goods store stocked with skins and hats, powder and pelts and fabrics. On the way upstairs to Missouri’s first capitol, they might stop to buy a brick of tea, the way suppliers sold it around here.

Upstairs the tiny governor’s office and the senate chamber flank the house of representatives with its rows of benches facing an 1804 King James Bible. Legislators stayed warm beside a stove at one end of the room, a fireplace at the other. Beef tallow candles offered dim light in these chambers, the cradle of democracy in a frontier state that would launch a million prairie schooners west.

Saint Charles was the waistband in the hourglass of westward expansion. If your ancestors migrated west, it’s a good bet they passed through Saint Charles, whether they were traveling by boat or overland trail.

The old customs house stands proudly on Main Street, just as it did when all westward travelers were obliged to stop to register. Sometimes they would spend the night in the customs house, especially on weekends, since the law prohibited traveling on Sunday.

–from Souls Along The Road

Share this Post