The bandit played his part like a trouper, quoting Shakespeare to his victims:

“I am joined with no foot-land-rakers, no long-staff sixpenny strikers, none of these mad mustachio purple-hued malt-worms, but with nobility and tranquility, burgomasters and great oneyers, such as can hold in, such as will strike sooner than speak, and speak sooner than drink, and drink sooner than pray, and yet, zounds, I lie, for they pray continually to their saint, the commonwealth, or rather not pray to her but prey on her, for they ride up and down on her and make her their boots.”

Frank James knew his lines. Boarding a railroad car at Gads Hill, Missouri, he quoted one of his favorite passages from Shakespeare, announcing to startled passengers his justification for the robbery. But just the rich, mind you. Not the working poor, with calloused hands. No women. No children.

In Henry IV Part I, the Bard describes that fat-kidneyed rascal Falstaff and a gang of highwaymen on the “Road by Gads-Hill.” The well-read Frank James might have favored that scene because it fit his disdain for fusty fat cats who rode the rails.

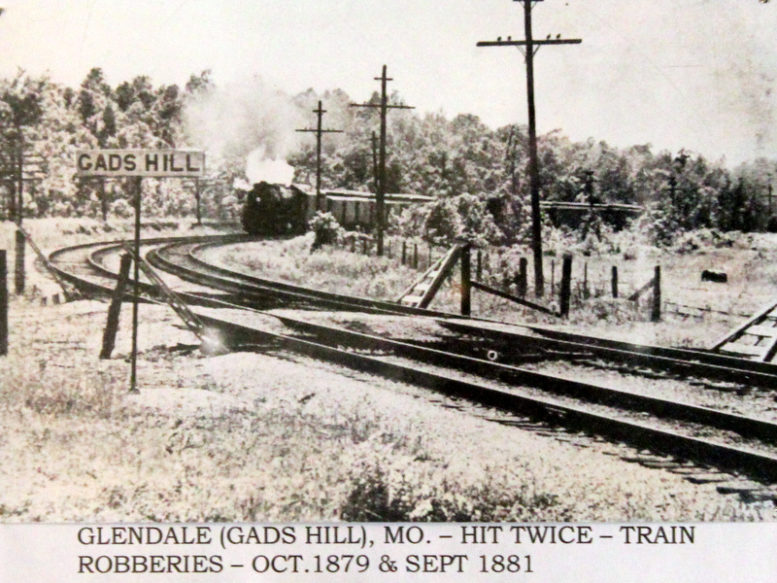

So why not stage a train robbery at Gads Hill, Missouri, conveniently located in the middle of nowhere?

That’s one theory, anyway. Since the bandits’ faces hid behind bandannas, witnesses and historians can’t be sure who quoted Henry IV during the robbery. Nor can they be sure what specific lines were quoted. That’s okay. Nobody is quite sure who wrote the play, either.

Gads Hill is barely a wide spot along the tracks of the St. Louis & Iron Mountain Southern Railroad. Some say the town is named for Charles Dickens’ English estate, Gads Hill Place. Maybe so. But Frank James knew that long before Dickens, the Bard said the Road by Gads Hill was a hangout for highwaymen who robbed travelers.

Often as not, trains didn’t stop in 1870s Gads Hill, Missouri. They just slowed to snag the mail sack from a trackside saloon. But on this afternoon, the southbound Little Rock Express planned to stop and discharge a passenger, even as the James Gang prepared to force it to stop.

Sarah Bernhardt would’ve chuckled, the way the robbers played the passengers, including Frank’s soliloquy about robbing nobility. At the conclusion of the plunder, one of the outlaws–likely Frank–handed over a written statement describing the robbery, muttering that newspapers had misreported details in some of the outlaws’ earlier exploits. Frank was a contemporary of Sarah Bernhardt, the hottest act in show business at the time and a capable self-publicist. Frank probably watched the success of Sarah Bernhardt’s self-promotion. It worked for Sarah; Frank could do it too.

So Frank wrote the first-ever robbers’ press release, which he handed to the startled conductor. It described the outlaws’ appearance and mischaracterized the general direction of their escape, thus forever casting doubt on the veracity of billions of subsequent news releases. Evidence suggests the gang escaped by heading west following the Black River, then the Current River. Eventually, Frank’s younger brother Jesse made it back to his betrothed, and they used his share of the loot to honeymoon on the Texas Riviera.

Nowadays, there’s not much at Gads Hill. A sign marks the spot where the outlaws stopped the train. The old saloon is gone, and a succession of local watering holes have come and gone, including a pub owned by a St. Louis publicist. Somewhere, Sarah Bernhardt is smiling.

Share this Post