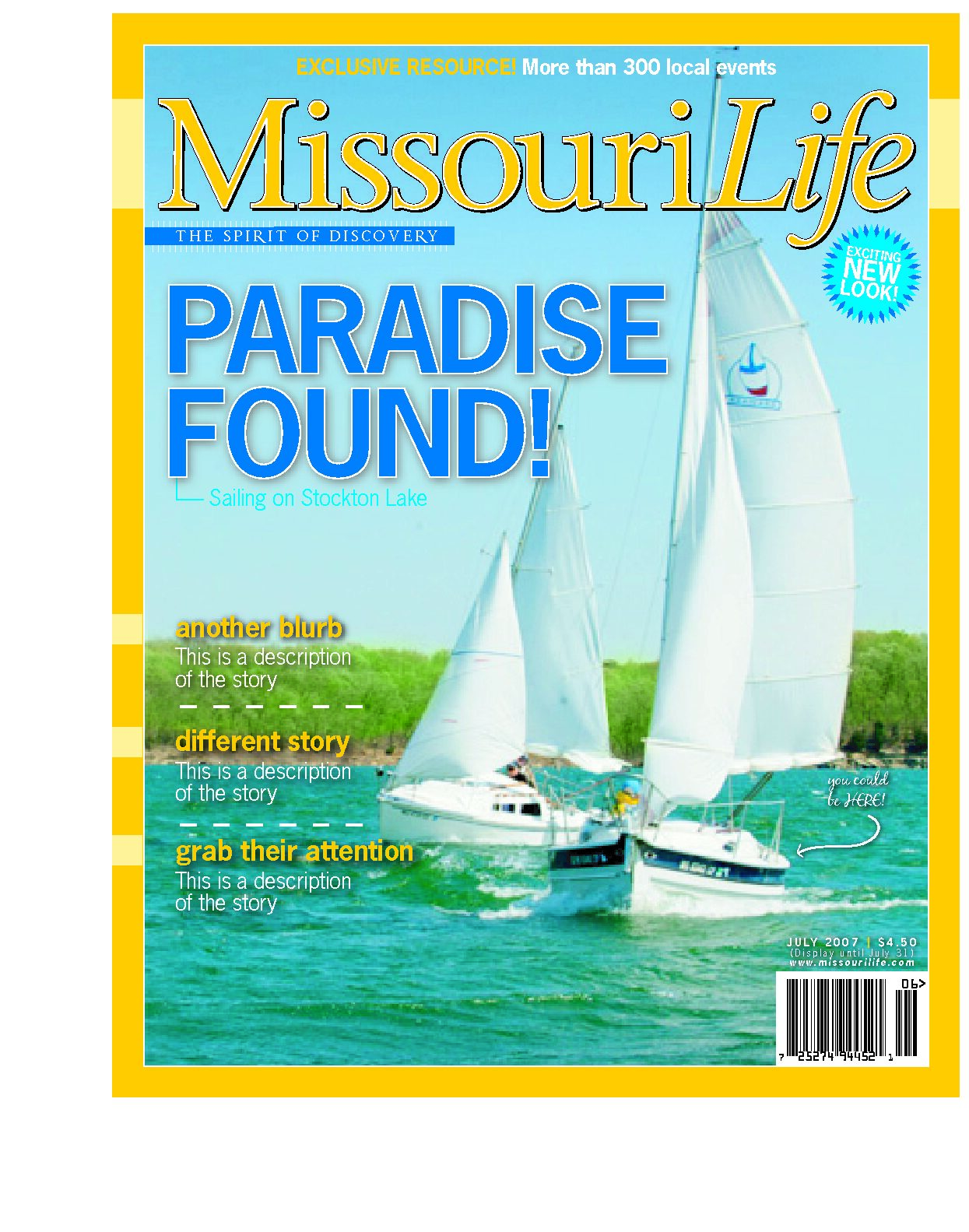

This is a peek at a Missouri Life Magazine cover coming together. I’m at the helm of the second boat. The day before, that boat was damn near sideways in a thirty-knot wind. The story was fun, sanitized a bit for the magazine.

Following is the unabridged account of the photo shoot, as told in Coastal Missouri.

Hard to believe, but it’s true. Missouri is a great place to sail. Some sailors say Stockton Lake is one of the top ten sailing lakes in the nation, but I couldn’t track down that rumor’s origin. No matter. Even if the Book of Revelations promised great sailing in Missouri, people would be skeptical. Can’t blame them. In Missouri, sailing might rank somewhere south of downhill skiing.

I chartered a sailboat on Stockton Lake and scheduled a photo shoot. As I drove south toward the lake to meet the photographer, whom I’d hired sight unseen, my cell phone buzzed. It was my photographer, saying he was being detained by a state trooper in Fair Play, Missouri, for running a stop sign, and for not having a valid driver’s license. He said the patrolman would release him to my custody. So I drove toward Fair Play. But before I reached that town, my cell phone buzzed again.

“Mr. Robinson, this is the Polk County Sheriff’s Department. We have your photographer here in jail, and he needs somebody to bond him out.”

Well then. I veered east to bail out my never-before-seen photographer. At the same time, a virulent squall line of storms ushered in a cold front from the north, dropping the temperature by thirty degrees in a matter of seconds. A stiff thirty-knot wind howled across my windshield. As we entered the town, a thunderstorm pounded us, offering strobe glimpses of the road between my wipers’ swipes.

When I reached the jail, a bondswoman said my photographer was in the process of posting his own bail and would be freed shortly. She introduced herself as Shanda and handed me a card: “Ass in a sling? Call Shanda’s Downtown Pawn & Bond.” I signed over my car as assurance my photographer would show up for trial. That wasn’t easy for me, risking Erifnus like that. Truth is, the car had barely enough monetary value to cover the bond. Erifnus Caitnop’s hail damage complexion has earned a salvage title, making her virtually worthless to anybody but me. But I needed a photographer, and with any luck and a little less wind, we’d be filming a sailboat in a couple of hours.

When he walked through the cell door, I stuck out my hand in the most unusual meeting I’d ever had with a photographer. Oh, it wasn’t the first time I bailed a photographer out of jail, just the first photographer I had to rescue before I’d had a chance to meet him.

Leaving the jail in Bolivar, I looked up at the cupola on the county courthouse, which appears to have a statue of Joan Collins on top. No, it’s not Simon Bolivar, for which the town is named. His statue stands, sword drawn, across from the Bolivar McDonald’s. Some things even Simon Bolivar could not conquer.

“Hungry?” I asked the photographer.

“Sure!”

I pointed to a sign advertising Cookin’ from Scratch restaurant. “Can’t go wrong there,” I said. We ate the local favorite: homemade Kelsey’s bologna, fried and slapped between two slices of bread. Then we headed for the lake. I saw a billboard with the question: “Ass in a sling?”

No longer, thanks to Shanda. And Erifnus.

***

We crested the hill overlooking the harbor at Stockton State Park Marina. My pulse quickened as I saw scores of masts, waiting patiently for mates to hoist a mainsail. Then I saw the waves. Outside the protection of the harbor, a mile of whitecaps waited like an army of Philistines.

Over the years on the seas, our sailing crew has battened down in a hurricane, and felt the sting of tropical storms. We’ve survived episodes with shredded sails and busted prop shafts and running aground, and fuel leaks inside hot diesel engines, and empty rum bottles with no refills in sight on the horizon. But we’ve never actually set sail in a thirty knot wind.

On our sailing adventures, Mike Dallmeyer is a trusted ally. More than that, he’s a good friend, and we’ve been through the kinds of scrapes that form a strong bond between high school buddies. Mike has been the captain on my vessel more often than not, but on this late afternoon, as we approached Stockton Lake to test the wind and waves, I was the captain. The decision to sail would be mine. The storm had blown over, but the trees still danced in a steady stiff wind, a constant near-gale that wailed and whistled between cars and buildings and boats bobbing at their marina moorings.

We walked down to the marina and greeted Chris Lefferts, half the tandem that manages the marina, lodge, cabins, and campgrounds. Her husband, Harry, scurried about the docks, supervising work crews preparing for the summer season. He stopped to huddle with us about weather conditions. Even though the storm had just passed, the wind continued to gust to thirty knots. That’s about the upper limit of sane sailing. We looked beyond the seawall that protects the harbor, and into a sea of whitecaps. I should’ve known better. I should’ve exercised caution. But hell, this is an inland lake, for God sakes. How bad could it get?

“You may want to wait until tomorrow,” Harry advised.

“I’d really like to get some shots today,” I persisted, thinking like a writer instead of like a sailor.

Undaunted, or maybe just too eager, we boarded our chartered twenty-two-foot Catalina and prepared the boat for sailing in strong winds. We reefed our mainsail, which shortens it, thus reducing the amount of wind it will catch and making it less likely that the boat will heel over and capsize. Ready for adventure, we cast off all lines. Harry wished us luck, and within a few minutes we hoisted the mainsail and glided past the seawall out into the open lake.

From way back in my memory, the phrase jumped into my conscious: “An inexperienced sailor will challenge a gale. A good sailor will handle it. A great sailor will wait on shore for better weather.”

There’s a reason they say that.

When we cleared the protection of the harbor’s seawall, the unabated wind hit us with a blast that laid the boat over, almost sideways. Mike struggled to hold the tiller. It took all his strength to guide the boat into the wind.

Meantime, we had a major problem flapping and flopping above our bow. I crawled out on the front deck as the boat pitched violently, and tried to gather a loose jib—that’s the triangular sail on the front of a sloop—and pin it down into the front hatch. Trying to overpower a loose sail in a gale force wind is asking to get flogged. I’d much prefer to piss into the wind. It actually was a benefit that the jib was loose, flapping like a flag rather than catching wind. It’s probably the only thing that kept the boat from capsizing. Harry circled us in a pontoon boat, yelling instructions we couldn’t hear in the howling wind, while the photographer, ballcap backward on his head, shot a hundred photos of Mike and me in various stages of wide-eyed panic.

After an hour of the most white-knuckle sailing I’d ever experienced, we retreated to safe harbor. The boat was unharmed, the sailors were wet and tired but whole, and the only thing damaged was the faith in my judgment. But I knew we got dramatic photos.

Sailing energizes the senses, especially that seventh sense: hunger. We drove nine miles into Stockton to break bread at Bongo’s, a delightful little restaurant specializing in Italian dishes and steaks. There, we sat down with Larry Strait, who operates the sailing school at Stockton Lake. With an easygoing manner and a gray beard, Larry exudes the wisdom you’d expect from an experienced sailing instructor. Wannabe sailors from throughout the Midwest seek Larry’s instruction. They get a conscientious teacher, who’s more interested in making sure students get plenty of time at the helm, rather than packing people on the boat like sardines. In a weekend, he can teach you basic sailing.

But he can’t fix an overzealous sailor.

He chuckled when I told him that today, we were outmatched by the wind. We swapped scary stories about the sea. And we ate. Then our photographer gave us the bad news: His film card was corrupted. No photos of white-knuckle sailing.

“I should have left you in jail,” I almost chided him. But I held my tongue, because, truth is, those photos should never have been attempted in the first place, not if I had been a great sailor. I was lucky the water spray off the lake didn’t ruin his whole camera. Our crew retreated to the state park’s cabins to recharge for the next day’s sail.

Next morning, we found the local gathering place, a breakfast grill in the back of a nearby convenience store. We inhaled a hot breakfast off of Styrofoam plates and cups and listened to the morning coffee council debate a range of issues, mostly related to fins and flippers.

Under sail by 10 a.m., we maneuvered alongside a local salt, Harry Rowe, who could sail circles around us in his smaller, faster sailboat. But it wasn’t the boat that was better than us; it was the sailor. We asked him if he competed in the Governor’s Cup Regatta held on this lake every October.

“Yes,” he replied, “I came in second a time or two. But it’s expensive.” He meant that racers take the Governor’s Cup seriously. They buy new sails and gear and prep their boats to get the best advantage.

Out of my league, I realized.

On this day, our photographer captured dramatic shots of the wind in our sails. One of his photos landed on a magazine cover.

Share this Post