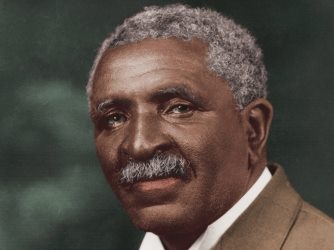

He made it a lifelong practice to demonstrate creative uses for things people normally throw in the garbage. He believed that nothing around the house should be discarded if it could be used.As such, George Washington Carver became America’s foremost recycler. “America has got to turn its attention in those directions to save what we have,” he said. He warned that destroying usable items was a lack of vision. “And where there is no vision,” he said, “people perish.”

“Everything on Earth has a purpose,” he told students. And Carver practiced what he preached. To illustrate this idea, he recounts one of his first days after leaving his alma mater, Iowa State University. He had accepted the invitation by Booker T. Washington to become the new director of agriculture studies at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. “I went to the trash pile at Tuskegee Institute and started my lab with bottles, old fruit jars and any other thing I found I could use.” From that trash, he built on a concept that guided his every move: “Nature produces no waste.” Amen, say the vultures.

George Carver was born outside tiny Diamond, Missouri, during the last shots of the Civil War. His childhood was turbulent. As an infant, he survived a kidnapping, and a bout with whooping cough which claimed his mother’s life. As a kid, he showed a talent for art. The farm’s owners, Moses and Susan Carver, sought education for George. They sent him to a childless black couple, Andrew and Mariah Watkins, who took him into their Neosho home, taught him values, nurtured his green thumb, and sent him on a path “with a satchel full of poverty and a burning zeal to know everything.”

As a young teen, his application for art school was accepted by a Kansas college. But when he showed up for classes, they saw he was black, and would not admit him. After similar ordeals, George found an open door at Simpson College in Iowa and then at Iowa A&M, the precursor to Iowa State University, where he switched his focus from painting to plants.

His legacy transcends mere peanuts. He became the grandfather of green, no less influential than John Muir or Teddy Roosevelt or Rachel Carson. He became America’s preeminent recycler, its patron saint of sustainable agriculture, and along the way its social conscience.

On the homestead where he was born sits the George Washington Carver National Monument, a scientific wonderland waiting for inquiring minds. In the middle of a restored prairie, it’s packed with enough common sense to save the world, equal parts Carver science, Carver care and Carver lifestyle.

Jerry and Barbara Hixenbaugh are local volunteers with as deep a passion for Carver as any paid staffer. They proudly showed me the museum’s new makeover, packed with more hands-on experiences than an oyster shucker.

It’s understandable that in America’s fast-food appetite for history, we know little more than peanuts about Carver. In too many instances, America’s collective knowledge about our icons gets boiled down to the substance of a slogan. Whole lives get reduced to tombstone histories, not enough information to fill a movie trailer.

Yet Carver was a trailblazer in agriculture, education, ecology, and life. Sure, he developed 300 uses for the lowly regarded peanut, making paper and ink, gasoline and shampoo, insecticide and nitroglycerin. No, he didn’t invent peanut butter. But he did develop 70 uses for pecans and 300 colored paints from clay. He made synthetic marble from wood pulp, paint from used motor oil, athlete’s foot medicine from persimmons, paving bricks from cotton, and stamp glue from sweet potato starch.

Few people realize that Carver saved the world from the ravages of cotton. He introduced the peanut plant as a rotation crop to give southern fields a break from a continual cotton crop which, year after year, had depleted soils. By planting peanuts in rotation with cotton, the peanut plant actually introduced nutrients back into the soil. Just as important, Carver’s idea to rotate the peanut crop with cotton dealt a blow to the boll weevil’s devastating grip on cotton country.

Jerry and Barbara showed me the trails young George Carver walked every morning. It was on these morning walks that he would “collect my floral beauties, and put them in my little garden I had hidden in the brush not far from the house, as it was considered foolishness in the neighborhood to waste time on flowers.”

Asked his secret to raising healthy plants, he responded simply, “Love them.”

–from A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart

Share this Post