Thomas Jefferson’s original grave marker can’t sit still. More than a century ago, it migrated from Monticello to Mizzou. Since then it has moved a couple of times on the campus quadrangle. I suspect Tom wouldn’t mind this movement, since his body rests in peace a thousand miles away. Besides, the curious positioning of a gravestone with no underlying body generates meaty conversation. The original Jefferson epitaph, which Tom wrote, lists his three proudest achievements: author of the Declaration of American Independence, author of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia.

Most Columbians know that Jefferson’s headstone sits on Francis Quadrangle, obtained fair and square with the blessing of Jefferson’s descendants. But beyond Tom’s tombless marker, it’s impossible to know the number of bodyless graves in Missouri. All we know are the stories about grave robbers, and thwarted attempts to steal some famous folks from Missouri soil.

Grave robbing is older than the pyramids, and humankind has spent much of its collective breath concocting curses and building booby traps to secure eternal peace. But body snatchers have the tenacity of water. They’ll find a way to seep in and do their damage. Body snatchers function as an unflattering mirror to society, since grave robbers march to one or all of the same three motivators that motivate most people: money, politics and religion.

Most of the grave robbers I’ve known confide that while their trade is generally regarded as beneath the honor of thieves, stealing valuables from a tomb is far less confrontational than stealing valuables from a live person. Certainly, the crime is less traumatic for the victim.

Many modern body snatchers perform the service in the name of science, to provide cadavers to medical researchers. A British study of recent body snatching episodes draws a parallel to grave robbers during the 1800s, who supplied stiffs to medical schools in sufficient numbers to keep anatomy students sawing away. Back then, body snatching became a cottage industry, with surgeons and students alike participating in robbing graves.

That was the case in Mark Twain’s era. Or at least, that was the case in Mark Twain’s mind.

Twain was fascinated by tales of body snatchers, and the subject shows up in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Two of his most cretinous characters, Injun Joe and Muff Potter, stole dead bodies from the local cemetery to feed the research needs of Dr. Robinson. Of course, when Injun Joe killed the doctor in that moonlit graveyard, scientific advancement came to a screeching halt.

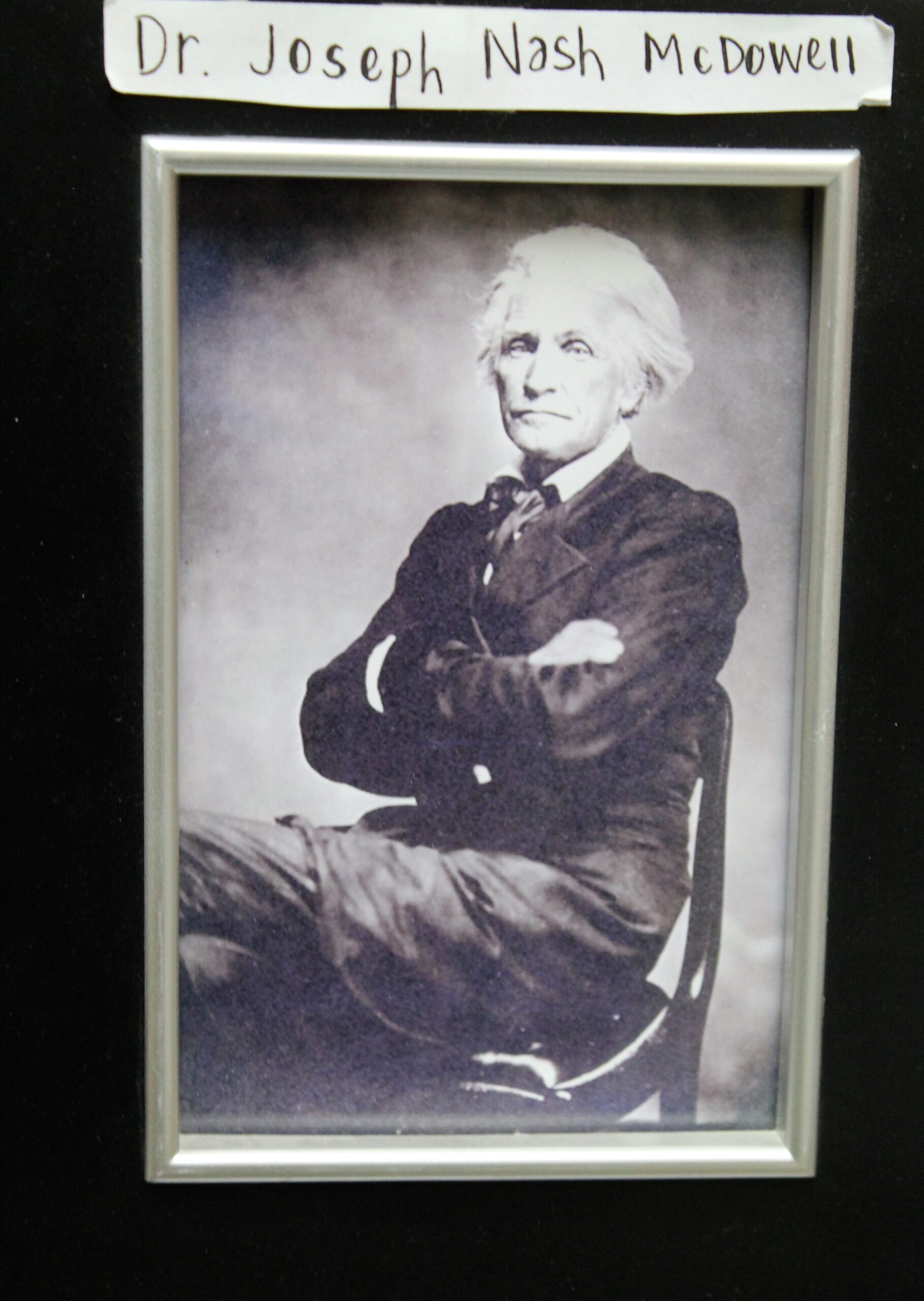

Twain patterned McDougal’s Cave in the Tom Sawyer story after McDowell’s Cave, which since has been renamed Mark Twain Cave. There, so the story goes, a real live Dr. McDowell bought the cave in the 1840s, walled the front entrance and used the cool cavern confines to perform research on corpses. Legend has it that local folks at the time were outraged when rumors persisted that one of the cadavers was the doctor’s own daughter, kept in a glass jar in the cave. Whether any of those tales were true or not, young Sam Clemens had a wealth of wild stories to draw from.

Undisturbed by time and tumult, Mark Twain’s body lies in Elmira, New York. Most Missourians accept the fact that this was Mark Twain’s wish. And even though living persons tend to be possessive of their dead, I haven’t heard of any attempts to steal Twain’s body and return him to Missouri.

Indeed, in the industry of snatching famous bodies, Missouri appears to be more exporter than importer.

Before there were cowboys in Missouri, or anywhere, there was Daniel Boone. He left droppings all over Missouri, and his namesakes spread liberally over the landscape.

Being the shy type, he made it his life’s work to stay one step ahead of urban sprawl. If neighbors encroached, he would pull up stakes, and leave for the wilderness. Daniel would have left Missouri by now, if he’d lived this long. But alas he died and was laid to rest in Marthasville, Missouri. He was content, I suppose, to lie there beside his beloved wife Rebecca. After his death, there’s some evidence that he may have left Missouri. Or maybe not. Kentuckians think they stole his body from its resting place. There’s some reasonable doubt. Buried as he was, next to his wife and a slave, locals speculate that the Kentuckians, easily confused by shell games, stole the wrong body. Scientists have proved this, using x-rays or divining rods or maybe they’re just bluffing. They know the servant was smaller than Daniel Boone. Or maybe he was larger. Anyway, some scientists suspect Kentucky stole the wrong body. Personally, I support science over Kentucky.

Regardless of what you believe, Marthasville keeps a bevy of buried treasures. Rebecca Boone is still buried there. Nobody stole Daniel’s lifelong partner, confidant, and by the way a damn able-bodied wilderness pioneer. She should be a saint, and it’s curious that there’s no Rebeccaville in Missouri.

–from A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart

Share this Post